After Agile, DevOps. What Now?

The Agile approach to software and product development has been around for something like fifteen years now. Its roots go back at least another fifteen years before that. In all that time, more and more folks have tried it out, and more and more of those folks have found it wanting in some degree. This presentation explains where Agile fits in the broader scope of organisation-wide effectiveness, and suggests what needs to change to move on from the Agile approach.

Effectiveness vs Efficiency

Rightshifting observes that most organisations are much less effective than they believe themselves to be, and much less effective than they could be. Let’s not confuse effectiveness with efficiency:

Effectiveness

Doing the right thing.

(creating & deploying value)

Efficiency

Doing the thing right.

(maximising the gain, minimising the cost)

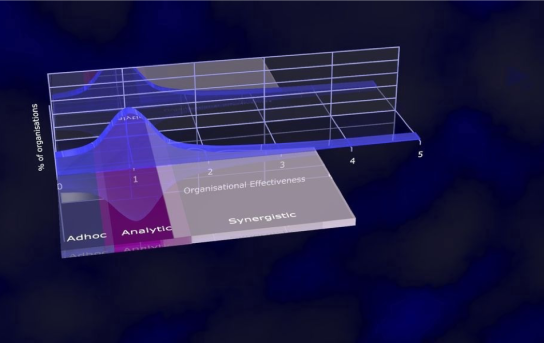

Normal Distribution Assumed

In the chart below, we see a distribution of all the world’s knowledge-work organisations, with respect to their relative effectiveness (horizontal axis). Most folks assume that it’s a normal bell-curve distribution, with some few ineffective organisations (to the left), some few highly-effective organisations (to the right), and the bulk of organisations somewhere in the “average” effectiveness centre ground:

In actuality, though, the distribution is highly skewed and looks like this:

Here (above) we see that fully half of all organisations have a relative effectiveness of less than one (the median), while there’s a long thin tail of increasingly effective organisations stretching out to the right (hence, “Rightshifting”). The most effective (rightmost) organisations are something like 5 times (500%!) more effective than the average (median).

Aside: For those interested in evidence, ISBSG data and NPS data correlate well to this distribution.

Waste (Non-Value Add) And Productivity

Overlaying lines for waste (a.k.a. muda: non-value-adding activities) and productivity on the above chart illustrates the consequences of such ineffectiveness. Median organisations for example are wasting around 75-80% of their time, effort, money and resources on doing things that add zero value from the perspective of any stakeholder:

So, how effective are those organisations that are using Agile (as intended)? Let’s look at where Agile fits on this chart:

As we can see, organisations using the Agile approach span the range circa 1.2 through 2.0. And that’s for organisations in which Agile is being done well. (There’s not much point talking about AINO – Agile in Name Only. That buys us nothing in the effectiveness stakes.) The exact position in this range of Agile’s effectiveness depends, in part, on how well the rest of the organisation is aligned to the Agile practices in e.g. the development, ops or DevOps groups within the organisation. Closer alignment = a more effective organisation as a whole.

From the above chart, we can see there’s a whole swathe of effectiveness (from circa 2.0 rightwards) not open to us through the application of the Agile approach. Organisations must find other approaches to access these higher levels of organisational effectiveness.

Explaining Effectiveness

So just what is it that accounts for any given organisation’s position on the Rightshifting Chart? What do the highly ineffective organisations to the left do differently from the average? What do the highly effective (Rightshifted) organisations do differently from the rest? What explains any and every organisation’s effectiveness? It’s very, very simple:

Effectiveness = f(Collective mindset)

That’s to say, any organisation’s effectiveness is a function of its collective, organisational mindset. A function of the assumptions and beliefs it holds in common about work, and how work should work. We can characterise the spectrum of organisation mindsets (a.k.a. memeplexes) into four basic categories: Adhoc, Analytic, Synergistic and Chaordic. This forms the essence of the Marshall Model.

The Adhoc Mindset

Least effective of all the mindsets is the Adhoc mindset. This is characterised by a near-complete absence of organisational structures and disciplines.

Adhoc-minded organisations have no managers, no processes, no standards and no accepted ways of doing things. Every day is more or less a new day, a clean slate, as far as running the business is concerned. In these organisations, the value of discipline has not yet been discovered. I like to think of these organisations in terms of the typical Mom-and-Pop family business.

Some of these organisations, of course – if they, for example, find a profitable niche in which to do their business – can grow despite their ineffectiveness. And with that growth, sooner or later, comes the realisation of the need for some discipline. At this time these organisations will likely start appointing managers, splitting the business into departments (silos) and thereby begin transitioning into the next mindset.

The Analytic Mindset

More effective than the Adhoc-minded organisations, those organisations with an Analytic mindset are typified by the corporates, large and small, that we have come to know and love(?) over the past one hundred years or so.

Central to the Analytic mindset is the belief that organisations are machines, and that just as with machines, if they are broken into parts, with each part performing well, then the whole will perform well. As Russell L. Ackoff (source for this sense of the term “analytic”) points out, this is a fallacy, although one very widely held in businesses everywhere.

Other common beliefs in the Analytic mindset include:

- Theory X (Douglas McGregor) – people are idle and shiftless and have to be beaten with a stick in order to get any work out of them.

- Extrinsic motivators such as perk and bonuses enhance performance (demonstrably false in knowledge-work).

- Managers do the thinking and workers do the doing.

- Check your humanity, emotions and passion at the door.

Eventually, a few organisations in pursuit of effectiveness may stumble – for it’s rarely intentional – out of the Analytic mindset and into the next mindset – Synergistic.

The Synergistic Mindset

The real uplift in effectiveness starts with an organisation’s transition into the Synergistic mindset. We’ve been hearing about some exemplars of this mindset for years (W.L. Gore, Semco) and others, more recently (Morning Star, Buurtzorg, et al.).

At the heart (sic) of the Synergistic mindset is the belief that organisations are much more like organisms than machines. Complex adaptive social systems rather than complicated yet predictable “mechanical” systems. The term “Synergistic” comes from R. Buckminster Fuller, and his statement that the performance of synergistic (synergetic) systems can never be predicted from an examination of their parts considered separately. This is not a comfortable concept for many of those more traditional business people.

Other common beliefs in the Synergistic mindset include:

- Theory Y (Douglas MgGregor) – people are keen to do a good job, if only they have the opportunity.

- Intrinsic motivation enhances performance (demonstrably true in knowledge-work).

- The people doing the work must decide how the work works.

- Alignment – and effectiveness – is a consequence of a shared, common purpose.

- Management – the social technology invented around one hundred years ago – is dead.

- Bring your humanity, emotions and passion with you into work, every day.

Eventually, a few organisations in pursuit of effectiveness may stumble – for, again, it’s rarely intentional – out of the Synergistic mindset and into the fourth and most effective organisational mindset – Chaordic.

The Chaordic Mindset

Most effective of all are those very few organisations embracing the Chaordic mindset.

Key to the Chaordic mindset is the continual, active, systematic searching for new business opportunities. The term “Chaordic” comes from Dee Hock – the originator of the Visa organisation back in the 1960’s.

The Chaordic mindset inherits from the Synergistic, with some additional common beliefs, including:

- Dynamic market sweet spots – tracking and exploiting the ever-changing high-margin sweet spots in the market.

- Instability – always teetering on the cusp between stability (order) and chaos (disorder).

- Inevitable collapse – occasionally, the organisation will collapse into (temporary) chaos and disorder.

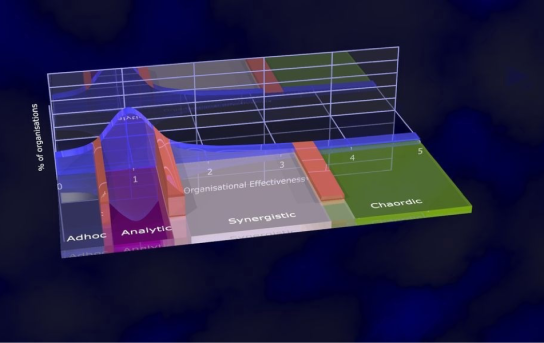

Transitions

Even more interesting than the four mindsets, though, are the three transitions (shown in orange, below). Each transition is an enormous wrench for most organisations.

The Adhoc to Analytic transition is relatively easy, going with the flow, as it were, in that wider society and most people in work mostly believe organisations should be run along the lines suggested by the Analytic mindset. Much more challenging are the other two transitions, being very counter-intuitive for most people.

Where Does Agile Fit In Terms Of Mindsets?

So, where does Agile fit amongst these four mindsets?

Here we can see how Agile straddles the Analytic-Synergistic transition. This explains just why sustainable Agile adoption is so difficult for most organisations. If part of the organisation makes the transition and the remaining parts do not, then Organisational Cognitive Dissonance ensues, and its eventual, inevitable resolution rarely results in the whole organisation shifting its mindset. Much more likely is either a) the now-synergistic part is dragged back, kicking and screaming, into the (old) Analytic ways of doing things or b) the (newly) synergistic folks find they cannot or will not go back, and thus quickly quit for pastures new.

From the above chart we can also see what is to come After Agile: More Synergistic thinking, more of an approach embracing the beliefs of the Synergistic mindset, and for some brave few, Chaordism.

– Bob